“Charles-Frédéric Brun, known as The Deserter, is a man of heights. His travels take him among the birch trees down below and the towards the larches high up. What are his thoughts as he shelters in the tranquil woodland, his bundle perched on his shoulder? From Haute-Nendaz he can see the plain and its gentle paths, the town, its stone houses and its church towers. Ahead he sees the vineyards carpeting the hillsides, as if Autumn had stood at the foot of the mountains and thrown a sumptuous blanket of gold leaf, vermillion and crimson across the hills.

Was he recalling the vineyards of Alsace and the opulence of the wine-growing villages there? Was he homesick for the country of his childhood, there in the high valleys?

His painter’s spirit was already sketching out an interior vision, the faces, the embroidered fabrics and flowers, always flowers. Today in his knapsack he has lots of blue, hardly any red left and some yellow for the background. Whatever. He sets himself up. He hardly needs any space. Gently, carefully, joyously, he blends the colours – with skill and with love because, after all, he is adorning a saint. He traces the contours of the picture with a confident, lavish hand.”

MARIE HÉRITIER

‘Les couleurs du Désert’ [‘The Colours of the Desert’], 2020

We’ll be walking alongside Charles-Frédéric Brun, known as The Deserter. He was a journeyman painter of the mid-19th century, and we can walk alongside him thanks to the work of some quite different creators:

→ Jean-Pierre Michelet (1873-1948), the storyteller

→ Jean Giono (1895-1970), the writer

→ Simon Tschopp and Daniel Varenne, graphic comic artists and storywriters (2020)/p>

![]() JEAN GIONO (1895-1970)

JEAN GIONO (1895-1970)

Jean Giono was born on 30th March 1895 in Manosque, a small town in Haute-Provence in southern France. His father, a shoemaker, was originally from the Piedmont region of Italy and his mother, who was a laundry woman, had ancestors in the Picardy region of northern France. Giono often recreated the atmosphere of his poor and happy childhood in his writings, referring to parents who “made a great fill of tenderness”. To help out with his parents’ financial situation, he cut short his studies in 1911 and got a job as a messenger at a local bank. He became passionate about reading, which propelled him towards writing. He was called up for national service in January 1915, and spent thirty months on the war front as a radio operator. He returned from the war unharmed, but the horror of what he had witnessed during the Great War never left him. Giono married Élise Maurin in 1920 and they had two daughters: Aline and Sylvie. He had his first inspired by Antiquity prose poems published in a Marseille review in 1922. He made the decisive acquaintance of the painter and poet Lucien Jacques, who introduced him to the Parisian literary scene. His first two novels were published in 1929: “Colline” (translated as ‘Hill of Destiny’) and “Un de Baumugnes” (translated as ‘Lovers are Never Losers’). They were enormously successful, and he quit his role in banking to live by the pen. His subsequent novels, “Le Chant du monde”, “Que ma joie demeure” (translated respectively as ‘The Song of the World’, ‘Joy of Man’s Desiring’) and his non-fiction work “Les Vraies Richesses” (‘The real riches’) exerted a great influence on young people of the 1930s who were anxious about another war breaking out. Giono’s influence was to continue making itself felt as he agitated for peace and revolted against industrial civilisation. Between 1935 and 1939 on the Contadour plateau in the Haute-Provence region of southern France, Giono brought people together, that included admirers of his and those who militated for a radical pacifism.

There were further trials as the 1939-1945 war came along: Giono spent two months in prison in 1939 as a result of his pacifist, anti-militarist activities. When Liberation came along in 1944, Giono was arrested for alleged collaboration with the occupying forces. No charges were laid against him, and he was freed after being held for five months. Banned from publishing anything until 1947, he returned to the literary scene thanks to six months of relentless work, during which his inspiration and writing was revived. Nature was always in the background in his works, which have unusual characters as their focus. Along came a succession of sombre-toned masterpieces, in which he depicted a tragic humanity coming to grips with hardships, writing in an ironic, light tone: “Un roi sans divertissement”, “Noé”, “Les Âmes fortes”, “Les Grands Chemins”, “Le Moulin de Pologne” (translated, respectively, as ‘A King without Diversion’, ‘Noah’, ‘Stout Souls’, ‘The Open Road’, and ‘The Malediction’). Giono found his place in the top tier of great novelists of the age in 1951, with the success of Hussard sur le toit (‘The Horseman on the Roof’) and in 1954 he joined the Academy Goncourt. His work became more varied – alongside novels such as “Le Bonheur fou”, “Ennemonde” and “L’Iris de Suse” (translated as ‘The Straw Man’, ‘Ennemonde’ and ‘Iris de Suse’) Giono also wrote the historical book Le Désastre de Pavie (‘The Battle of Pavia’) as well as a number of articles, prefaces and journalistic pieces, devoting himself to the theatre and cinema that had so enthralled him since his youth. He produced “Crésus” in 1960 with the French actor Fernandel, and died on 9 October 1970 at Manosque in the Provence region of France.

JACQUES MÉNY

President of the Association of the Friends of Jean Giono

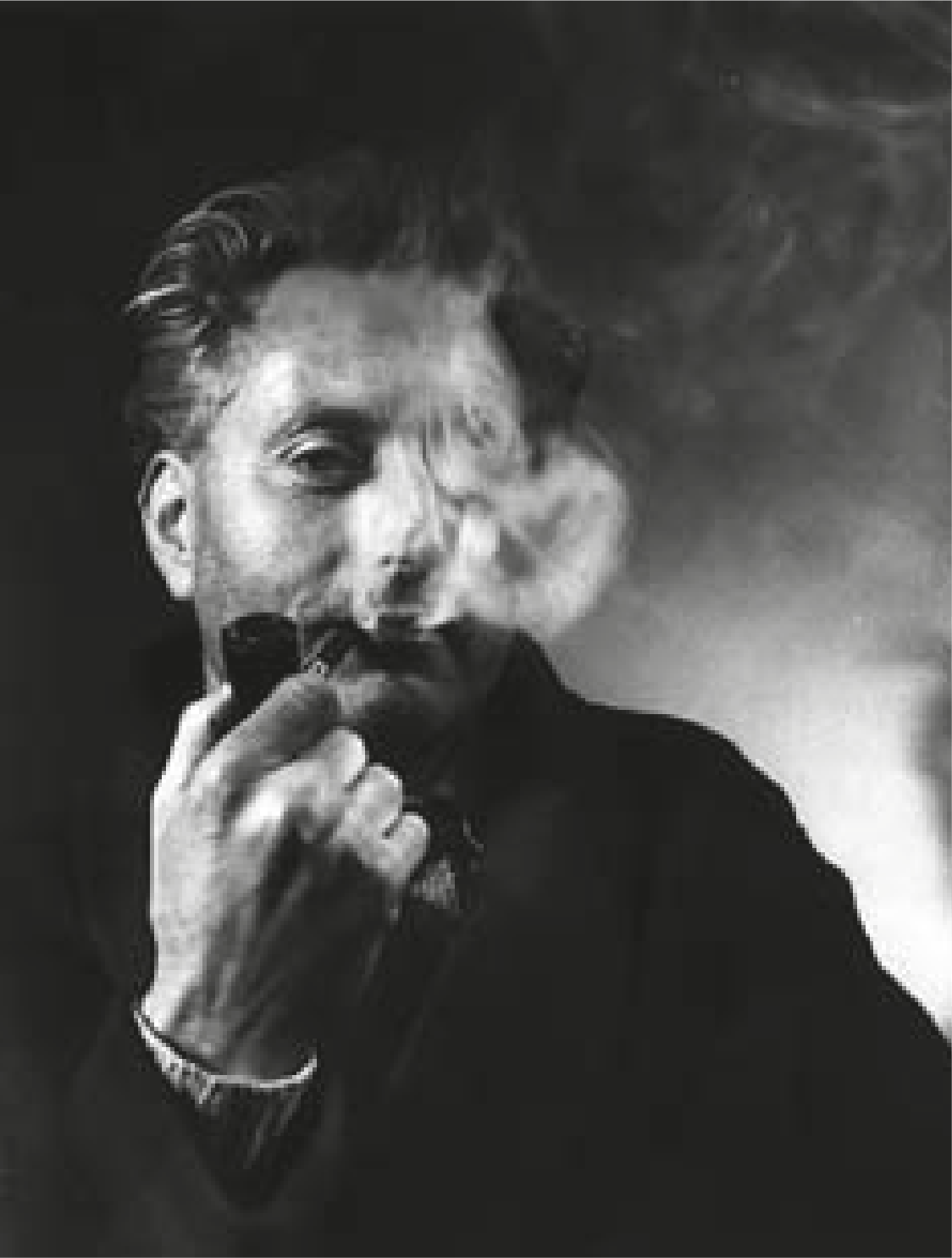

![]() The Deserter by Jean Giono

The Deserter by Jean Giono

EIn October 1964, the creator and visual artist René Creux suggested to Jean Giono that he write the story of Charles-Frédéric Brun, known as ‘The Deserter’, as an introduction to the work that he wanted to publish on the output of this ‘extraordinary illustrator’. The mysterious figure appealed to Giono, and he invited René Creux to Manosque. Less than a year later, on 19 October 1965, he told Creux that he had “completed the final sentence on the story of the Deserter”, and considered that he had written a “great piece of writing” about him: “I have given the Deserter the character he must have had and, as far as I could manage it, the character he in fact had.”

Le Déserteur is one of Giono’s final great pieces of writing. Giono died in October 1970, less than a year after completing “L’Iris de Suse” – his final masterpiece that is the story of a desertion that owes a lot to his writing on Charles-Frédéric Brun. Giono was immediately captivated by The Deserter, and that is because the character was part of the same family of people as other characters that had long filled his creative imagination and his works: wanderers, artist-healers, solitary heroes who deserted “the business of the world” and those who discarded the trappings of society.

Contrary to what he had mischievously told René Creux, Giono had never spent a week incognito in Le Valais following the footsteps of CharlesFrédéric Brun, nor had he made inquiries with his daughter and sonin-law. But he had the ability to furnish innumerable accurate and precise details in describing a landscape based on photographs and postcards. René Creux had given Giono plenty of paperwork on the subject including “Valais 26 itinéraires” (‘Valais – 26 itineraries’) by André Beerli, which meant that the novelist could convincingly tell the story of the life and journeys of the Deserter, making of him a novelistic hero. In the shadow of the penmanship of Charles-Frédéric Brun, Giono too sketched out a portrait of a solitary artist taking refuge in the heights of his work.

The Swiss writer Charles-François Landry was not wrong when he wrote: “Right from the first glimpse, Giono understood what his business was, his unswerving business: the human always went far beyond the painter in this internal adventure that was The Deserter. Important as the work of The Deserter was, the deserter’s life as conjured up by Giono is a work that is ten, twenty times more significant.” Charles-Frédéric Brun, that ‘character of Victor Hugo’ who ‘was from the world of “Les Misérables” before it was even conceived” as Giono wrote in the opening part of his story, has gone on to become a core figure in his work for all time, one of the greatest in 20th century literature.

The Deserter by Jean Giono was published in 1966, and Franco Maria Ricci published the text in Italian (see cover, above). Giono’s text went on to be published in Italian, German, Polish and Romanian, and 17 different editions were published between 1966 and 2009.

JACQUES MÉNY

President of the Association of the Friends of Jean Giono

PATOIS

– A câ rë sta màta ? chi maton ? Whose is this girl? this boy?

– A Lucienne de Marie-Antoinette de Priïn !

They belong to Lucienne of Marie-Antoinette of Cyprien.

People from Nendaz traditionally introduced themselves using the names of parents and grandparents as a way of positioning themselves within the family’s ancestry.

![]() Why would an illustrator – an artist working on paper – want to flee the riches of Alsace to take refuge in the mountains of central Valais?

Why would an illustrator – an artist working on paper – want to flee the riches of Alsace to take refuge in the mountains of central Valais?

If you were to go on a trip on foot that lasted several days, without being able to buy any-thing along the way and with just five things in your backpack, what would you choose to take?